-

Harry Begg

Max Weber Fellow

Max Weber Programme for Postdoctoral Studies

Max Weber Fellow

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Read more

News

First contributions to the Banking Supervision Policy Working Paper Series

The Florence School of Banking and Finance published the first papers of the new Banking Supervision Policy Working Paper Series, launched as part of the partnership with the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), to promote...

Can AI be effectively leveraged for financial stability or will governments remain mostly reactive to the force of technological change led by big companies?

With colleagues, I have been working with large language models (LLMs) to understand how the mass media writes about banking and finance. Specifically, we have built a dataset of over 550,000 newspaper articles about banking published in 6 major democracies in the decade-plus period during and after the Global Financial Crisis (2006-2018). We’ve invested this time because we think mass media trends reveal important information about what’s going on in financial markets, and policymaking and democracy more generally.

To demonstrate our work at a high level, we trained an LLM to classify articles according to different categories of political and regulatory interest. After much human input and fine-tuning the LLM is now pretty effective at recognising whether a news article is about a scandal, a regulation, bank capital, liquidity or a number of other topics relevant to our interests.

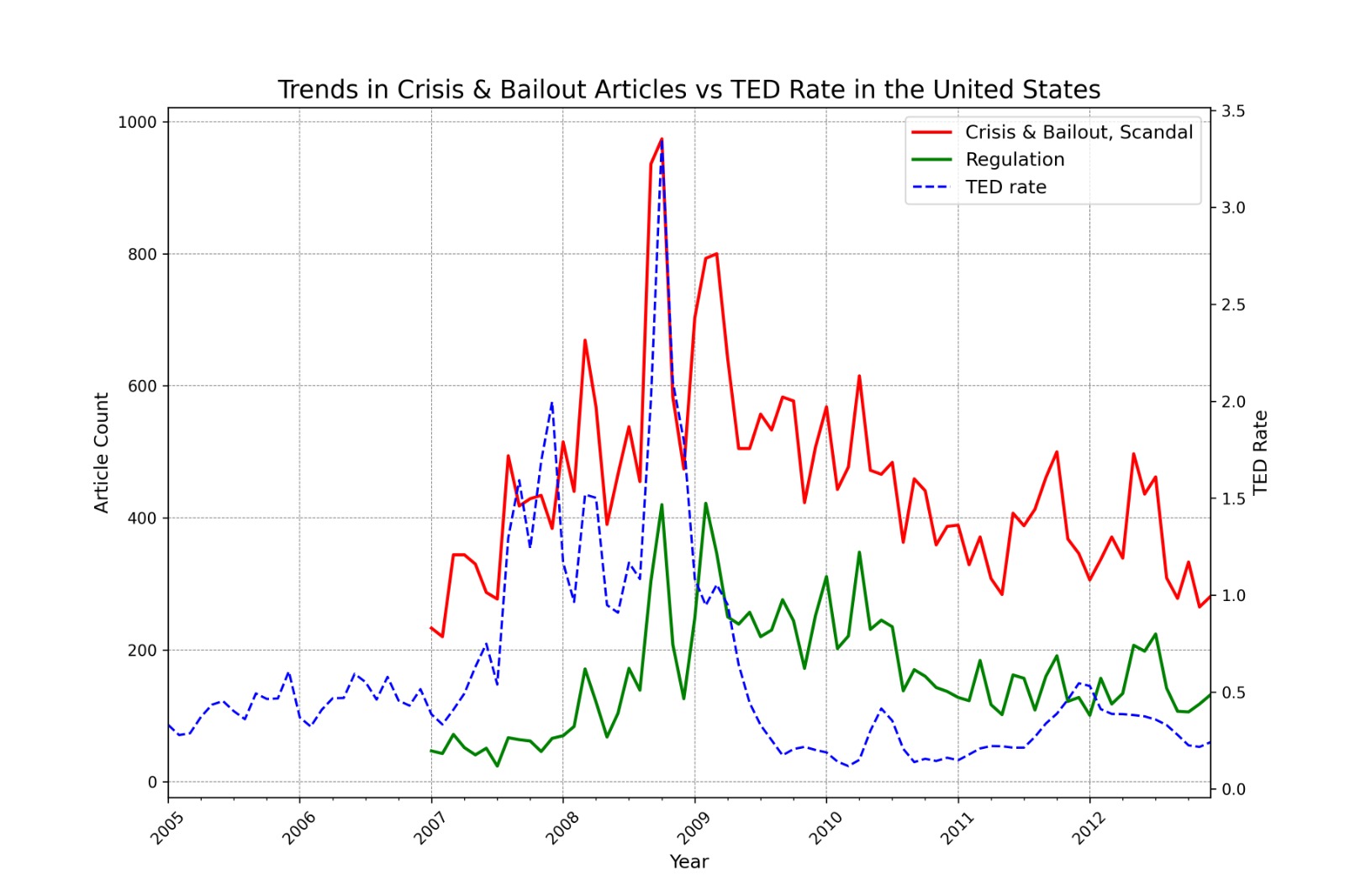

The graph below shows what these trends look like at the macro-level in the United States. As can be seen, media coverage of crisis-related categories (Scandal and Crisis & Bailouts) is highly correlated with the TED rate (until the recent phasing-out of Libor, the TED rate was a key measure of market risk, calculated as the difference between the interest rate on short-term interbank loans and the three-month US Treasury Bill rate). After the crisis high-point, media trends in these categories continue at what appear to be historically high rates. Media attention to post-crisis regulation also surges, while the TED rate declines (at least partly due to bank bailouts).

So far, so intuitive. But if this is what can be got out of a macro-analysis for our specific (social science) research project, just think what regulators and supervisors could achieve with more fine-grained categories tailor-made to their specific tasks and demands.

In 2023, for example, several mid-size American banks and the Swiss G-SIB Credit Suisse, failed. As everyone reading this post will remember, these failures played out at an unprecedented pace, not just in newspapers but also via social media. Regulators had to react extraordinarily quickly as deposits were withdrawn, to a significant extent as a result of information consumers received from social and news media coverage.

If regulators are to effectively adapt to this fast-paced information-saturated world they need to know how specific narratives are developing in the public domain that may have a bearing on financial stability.

No one is saying that governments will be able to compete with the innovative capacity of the private sector in AI development. There will need to be training, collaboration and knowledge-sharing. But rather than seeing AI as an exogenous force to respond to, governments need to jump in with both feet to understand both the promise and the perils of these powerful new technologies.